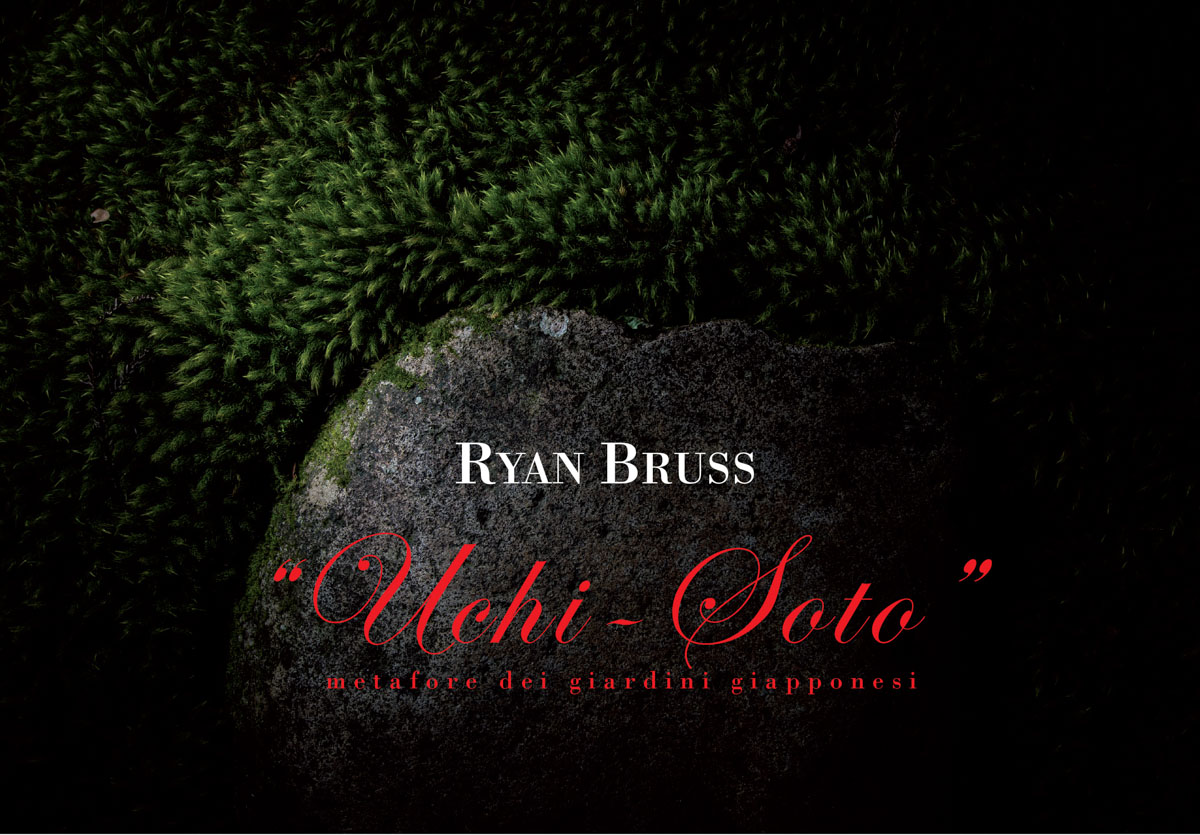

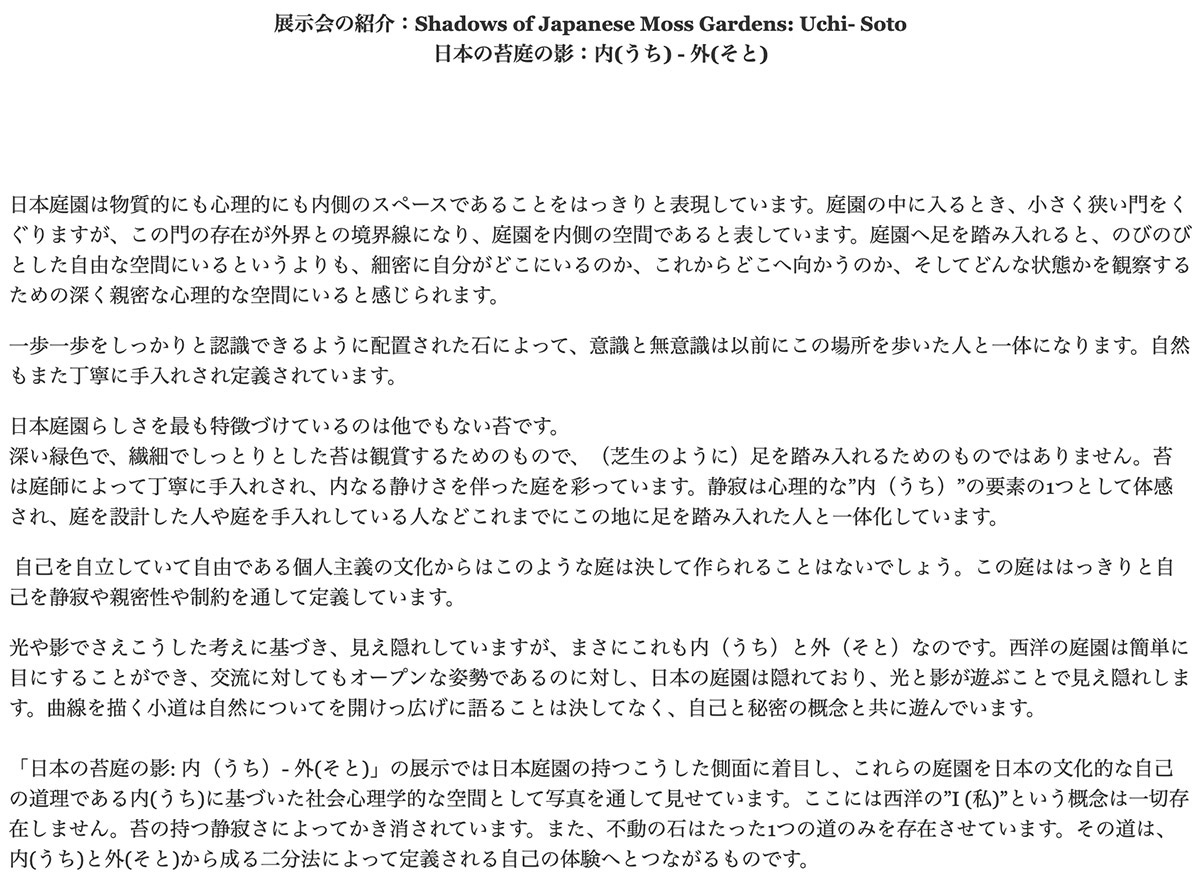

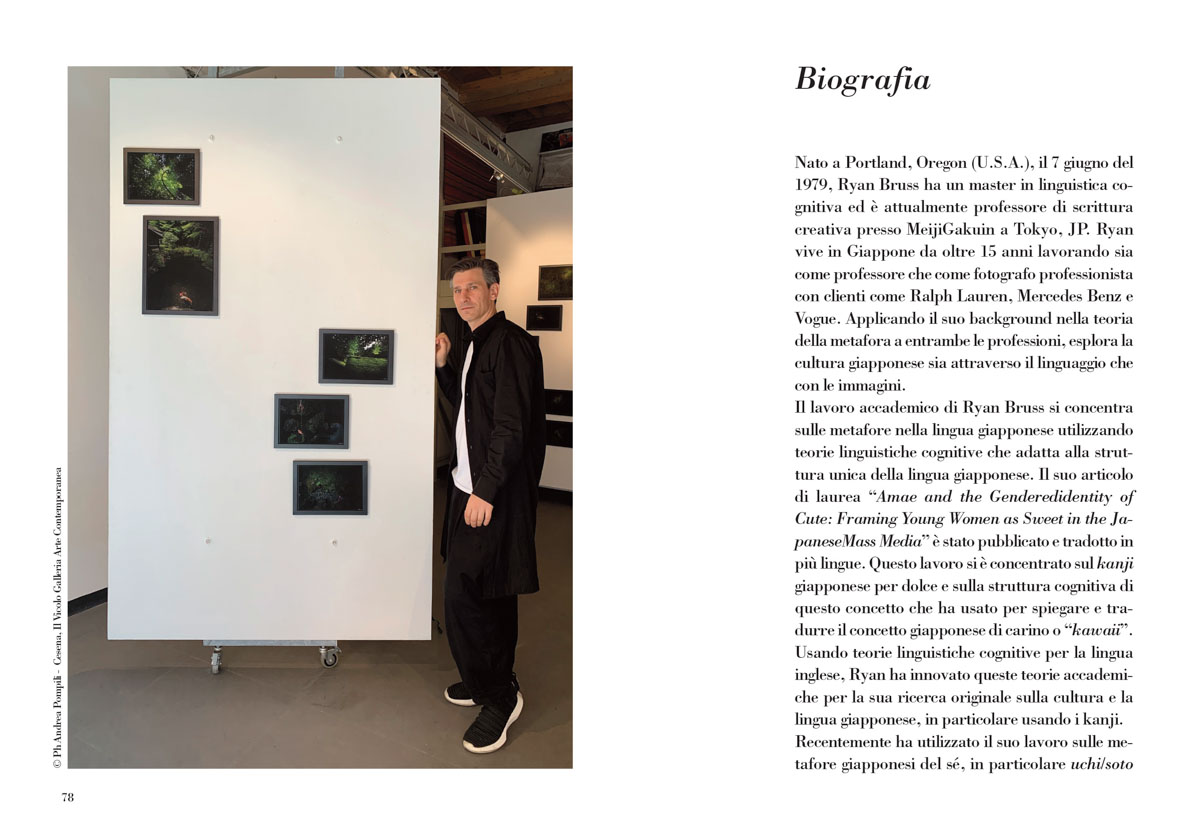

About This Project

Essay: The Japanese Cultural Logic of the Self and Space:

Uchi/Soto & Japanese gardens

In any discourse, there is a referential anchor that is created. The interlocutors and audience must imagine the reference point in relation to which the discourse is related spatially, temporally, socially, and psychologically. This is a universal quality of language which Benveniste refers to as the subject. “In some way language puts forth ‘empty’ forms which each speaker, in the exercise of discourse, appropriates to himself and which he relates to his ‘person,’ at the same time defining himself as I and a partner as you.” [1] The subject is the self as understood through the discourse. The self acts as the perspective, or deictic anchor, that is the reference point for the conceptual framework which is constructed through discourse or deixis. This process is particularly evident in the use of personal pronouns, which directly reference the concept of the self. The self is a culturally dependent concept and different cultures have different metaphors by which the self is understood. Within the Western philosophical tradition it has long been assumed that this anchor of discourse, the self, was universal in nature and a neutral concept: I. Japanese presents a culture whose discourse and language is structured around a divergent concept of the self. This essay briefly introduces the concept of self as understood in the West through the use of personal pronouns, which represent a system of reference based on an individual, ego-centric deictic anchor. This definition of deixis will then be re-examined from the Japanese cultural perspective of the self and the concept of uchi as the deictic anchor which structures their system of personal pronouns and discourse.

The concept of self as uchi will then be applied to an analysis of the meaning of Japanese gardens and the accompanying exhibition “Shadows of Japanese Moss Gardens: Uchi- Soto.” Japanese gardens will be explained as specific cultural constructs built out of the Japanese concept of the self: uchi. Instinctually the feel of a Japanese garden is divergent from Western gardens. Western gardens are defined by freedom; freedom of movement, both of the interloctor and the plants themselves. Entering a western garden, it is an extension of the outside and once inside you are free to roam as I. The grass, trees, flowers, all the elements of the garden itself are also generally left to nature, openness and light fill the garden. To enter the deep shadows of a Japanese garden, however, is to enter a divergent discourse on the nature of the self, a defined physical, social, and psychological space centered around the concept of uchi.

Uchi as Subject

According to Lyons, deixis can be defined as “the location and identification of persons, objects, events, processes, and activities being talked about, or referred to, in relation to the spacio-temporal context created and sustained by the act of utterance and participation in it, typically of a single speaker and at least some addressee.”[2] As Wetzel points out, this definition defines the deictic anchor as a fixed location: I.[3] In Western discourse the concept of ego and self is synonymous with I. “I refers to the act of individual discourse in which it is pronounced, and by this it designates the speaker” or the self outside of the discourse.”[4] Japanese discourse represents a challenge to the universal nature of the Western deictic anchor: I. In Japanese discourse, the subject is not I because the self is not conceptualized as a fixed ego, nor universally individualistic. The self and other are described in Japanese language in terms of a social-psychological space of involvement: uchi. The reason uchi is used to describe this concept is the extensive usage of uchi nominally to describe not only the self, but also social, temporal, and spatial location. In this sense, uchi is literally the deictic anchor of speech as all of these domains are nominally referred to as uchi. The concept of uchi literally means “internal,” however, it is used in many other ways to structure the language by which the self is located. The following are examples of some of the ways in which this concept is used spatially, socially, and temporally to refer to a perspective in discourse: inside the room, inside field (infield), inside brother (my brother), inside university (my university), inside-inside (my family), inside youth (while I am young). In examining the specific metaphor for the self, UCHI as SELF, the concept of uchi can be categorized into two different image-schema. The first conceptual structure is based on an internal perspective and will be referred to as the Internal Containment Metaphor. Spatial examples of this understanding of uchi are: 内圧, 内法, 内掘, 内部, 内開き, 内池. In the second conceptual structure, referred to as the External Containment Metaphor, the perspective is from the outside. Examples of this metaphor are: 内惑星, 内野, 内陸国, 内回り, 内耳). Uchi is used nominally, as well as conceptually within syntax, to describe the self and social relativity based on these two metaphors which offer different perspectives. Uchi is used to specifically references the psychological, physical, and social self from these two perspectives. The Internal Containment metaphor is the more commonly used and is seen in the following examples to define the self:

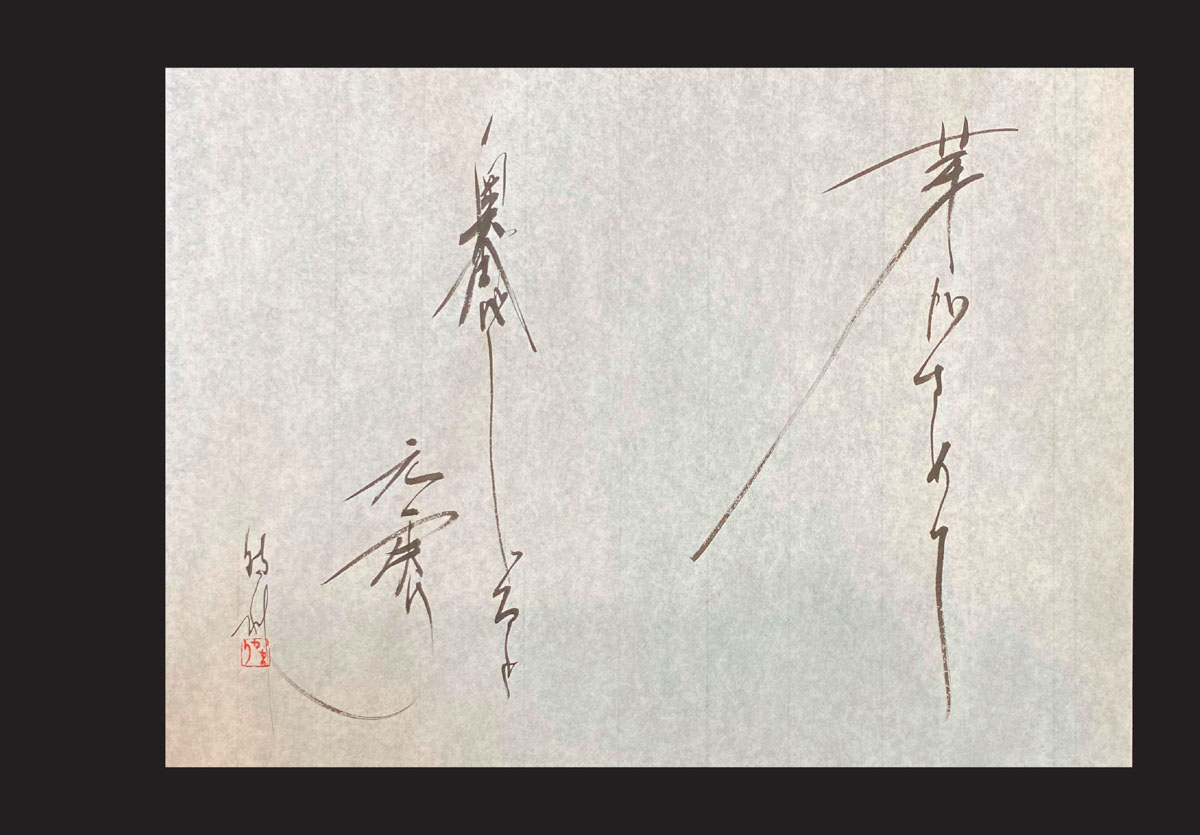

- Internal Psychological: (内気, 内観, 内向性, 内に秘めっている(気持ち))

- Internal Physical: (内科, 内臓, 内出血)

- Internal Social: (内輪, 内外, 内用, 内乱, 内国, 内通者)

These are all examples of the physical or psychological self as understood in terms of uchi, the most common usage of uchi, however, is in describing the self as a social group. Uchi can be paired with the words university, family, father/mother, siblings, team, friends, and many other auxiliary nouns which defines a social group that the individual is a part of. The translation of uchi in this linguistic context is my, which can also used as a plural personal pronoun, our. In the internal social examples listed above, the flexible nature of the concept of uchi is highlighted. In the first instances, the individual-self was the containment boundary, while in these examples above the social group the individual is a part of is the containment boundary. The self in all instances is understood in terms of the unified internal space, which has led to the argument that in Japanese there is no individual conception of the self, but that the self is always understood as part of a social group. The individual can also join or leave social-inside spaces as seen in these phrases: わたしを入れて, 仲間 外れ.

The second metaphor, External Containment, however, shows that the self can also be understood as an independent entity with an internal and external dimension, though the self is still understood in relation to a social-psychological context. The following list are examples of the binary nature of the internal/external self described nominally by uchi. In each of these examples there are two aspects of the self. The private/public or true/false self. This is the case for the last example, uchi-uchi or private which highlights the two concepts of uchi. On the one hand the self an uchi-group constrasted with the other, but there are also uchi-soto aspects within the self as an individual. Social groups are also described in terms of the External Containment metaphor of uchi. The external social self examples show compound nouns which pick out an uchi-group as part of a larger social group which the soto-group is also a part of from an external perspective.

- External Psychological: (内懐, 内心)

- External Social Self: (内内で, 内局, 内聞の, 内陣, 内謁, 内閣, 内祝言, 内輪)

In defining the concept of the self in terms of uchi, there are two important entailments within discourse. The subject as constructed in Japanese discourse: 1) has a movable ego, or perspective, that shifts within the context of uchi; 2) The self (and other) are located in a fluid social-psychological space of either inclusion or exclusion. Uchi as the deictic anchor redefines the concept of deixis as the location and identification of persons, objects, events, processes, and activities being talked about, or referred to, in relation to the fluid spatial, temporal, social, and psychological context created and sustained by the act of utterance and participation in it by the interlocutors and addressee(s) present. The Japanese system of personal pronouns also reflects the Japanese logic of self in referring to uchi not I as the subject. The words for I (僕、私、おれ、わし、われ、内 ) and You ( あなた、きみ、あんた、おまえ、てめえ、おのれ、貴様) all define a different perspective on uchi and where the interlocutors are located in relationship to this space. In a meta-semantic and meta-pragmatic analysis of Japanese subject, object, and reflexive personal pronouns, the meaning of the Japanese system of referencing the subject can only be understood in terms of uchi.

Conclusion & Cultural Application of Uchi Metaphor:

Japanese Gardens & the Self

Through this analysis of the conceptual structure underlying the Japanese language, as well as other research which has concentrated on uchi, the concept of a universal deictic anchor becomes highly problematic because of the relative nature of the self. In the West, the understanding of self as I, dictates a system of personal pronouns which are based on the idea of the self as an individual and the fixed location of the ego. The self and other are derived from the referent’s ego. In contrast, the Japanese cultural logic of the self is based on the concept of uchi, which defines the self as either an autonomous social-psychological space with internal/external aspects or a unified social-psychological space. In each case the understanding of the self is based on a social-psychological context. At both a meta-semantic and meta-pragmatic level this social-psychological space is the deictic anchor of Japanese discourse and language which re-defines Benveniste’s concept of the subject.

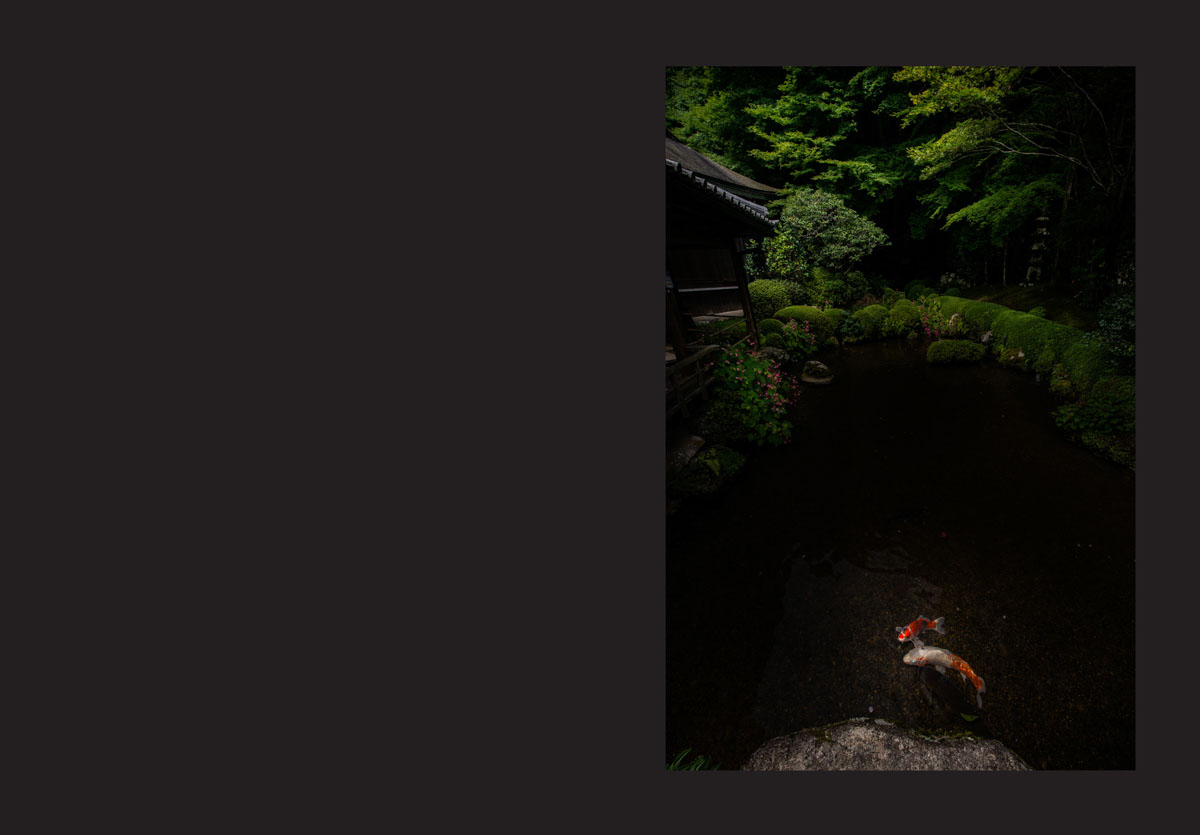

It is in this definition of the subject as uchi that Japanese gardens begin to make sense and reveal their nature as expression of the Japanese cultural logic of the self: uchi. Walking through the tiny door at the entrance forces one to bow down and the self, the referential anchor of discourse, is redefined. The wooden gate at the entrance is small and constrictive delineating the garden as an inside space. One`s concept of self is forced into a new understanding, one that is based on the concept of uchi, in this case a social-psychological space of inclusion. Indeed several of the terms which use the concept uchi refer to this experience, 内開き and 内池. The door opens to an internal physical, social, and psychological space.

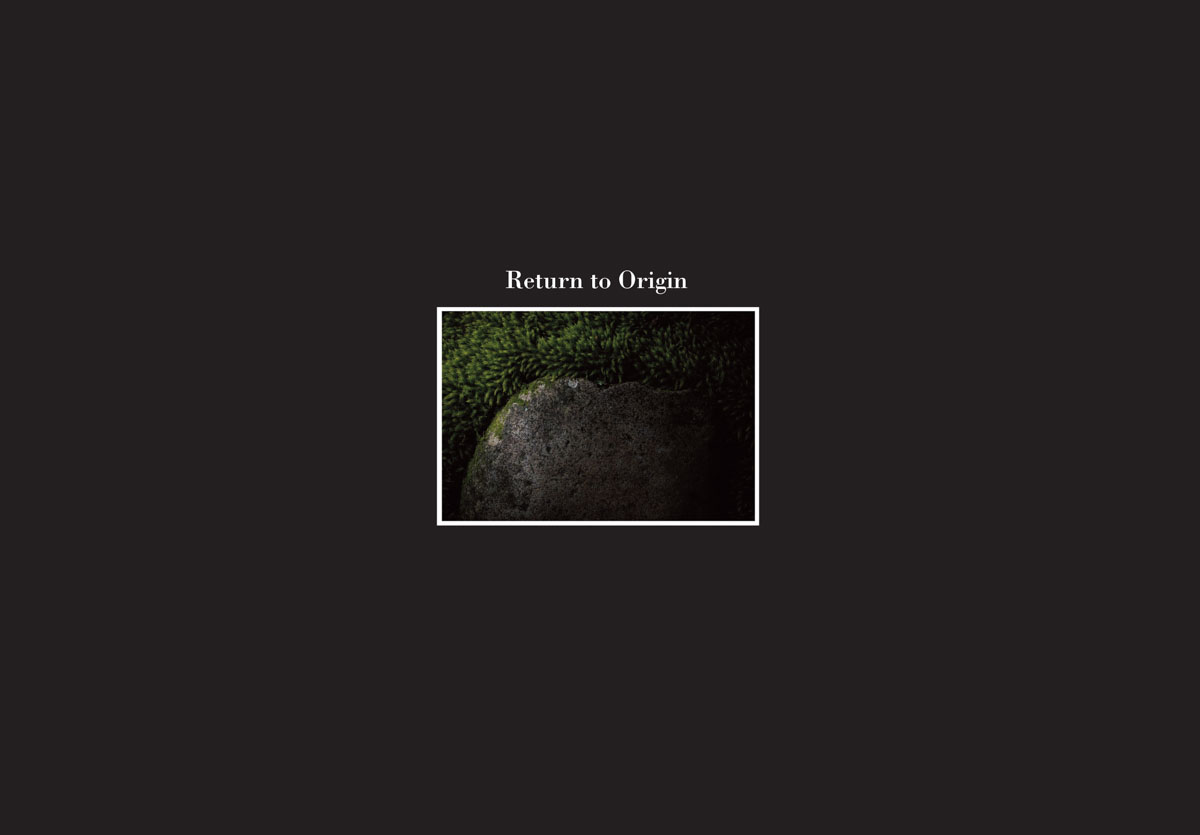

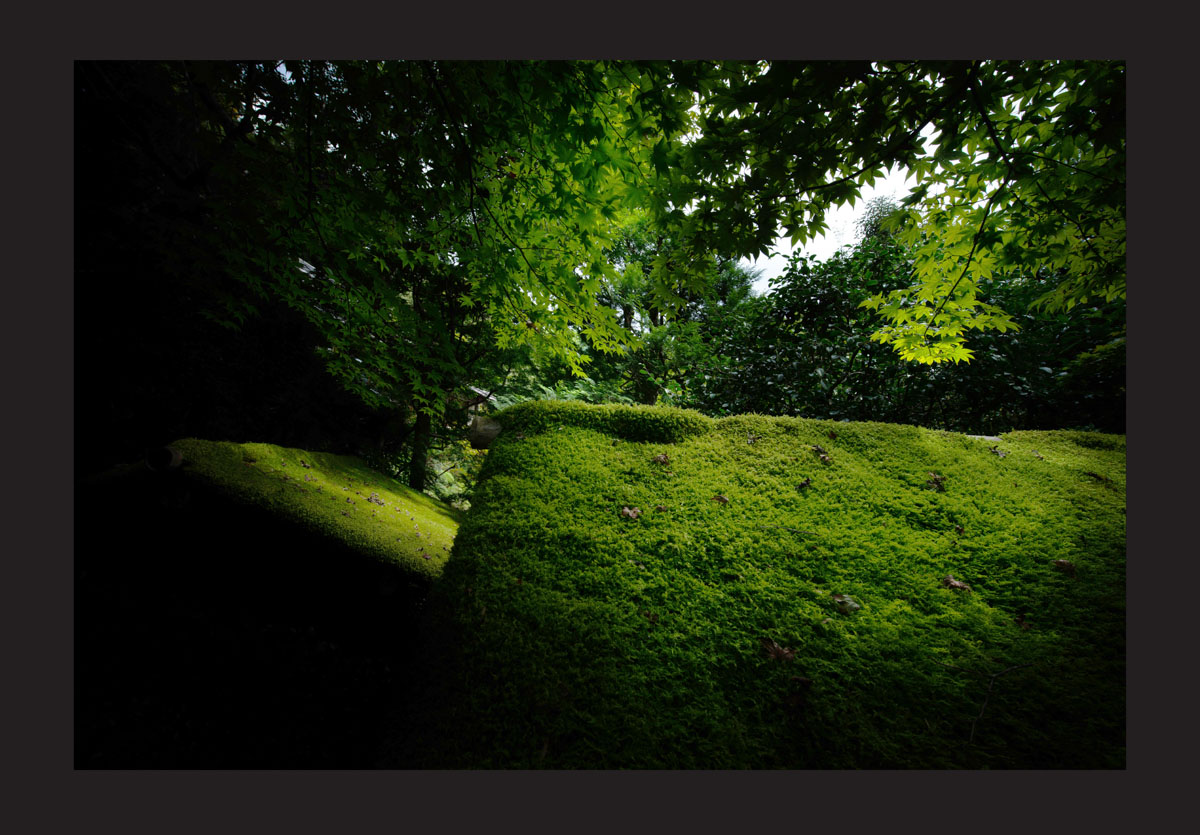

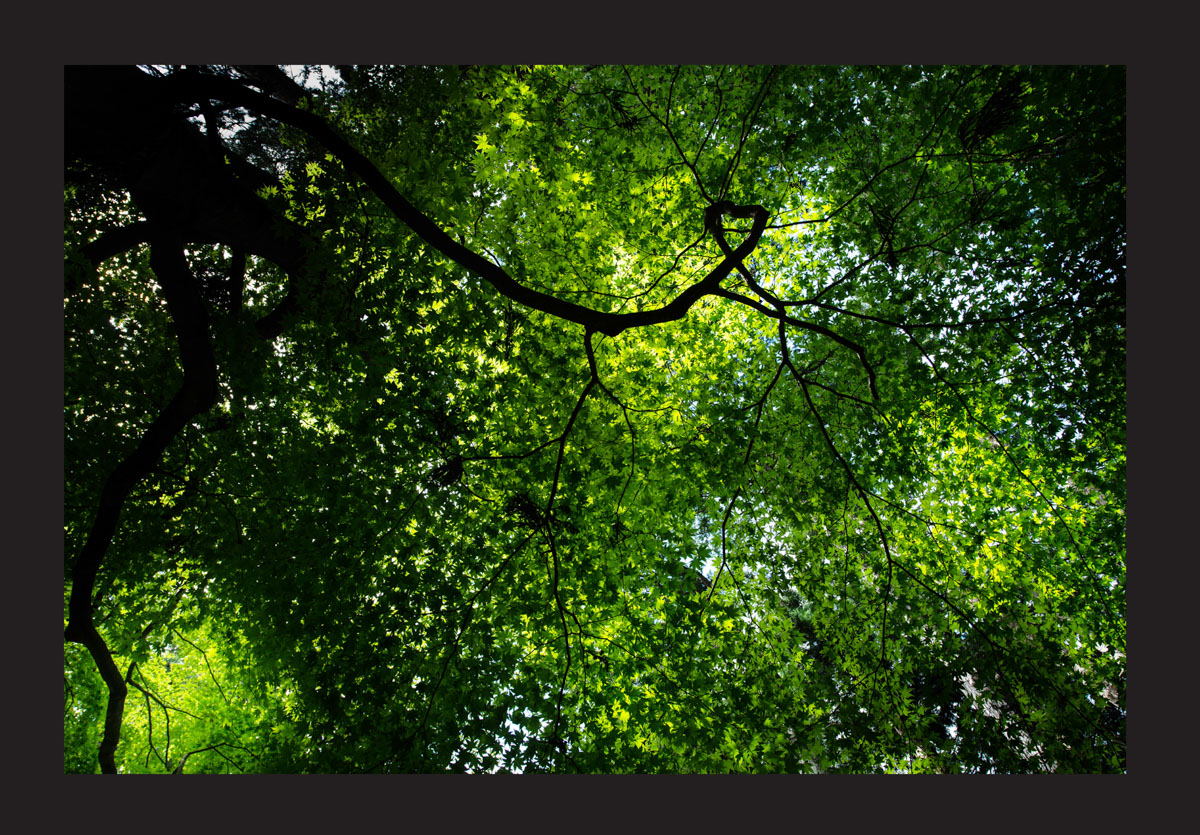

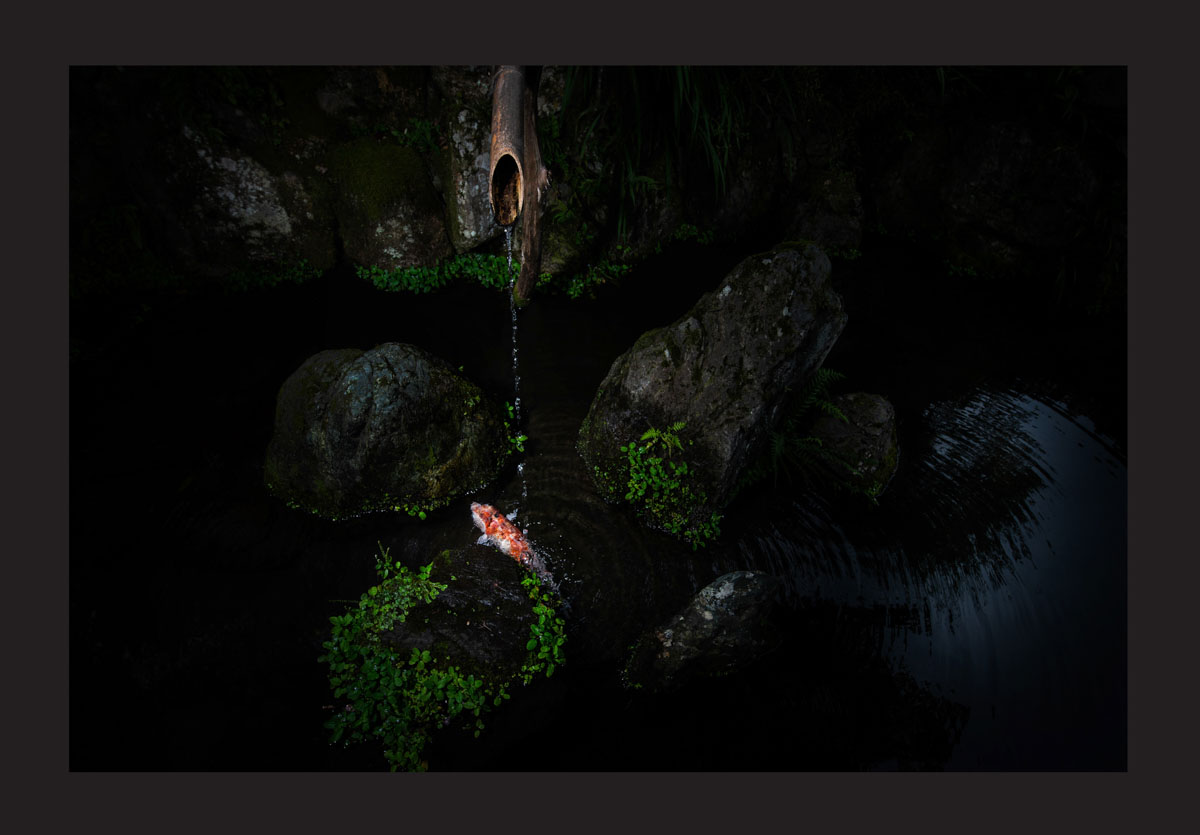

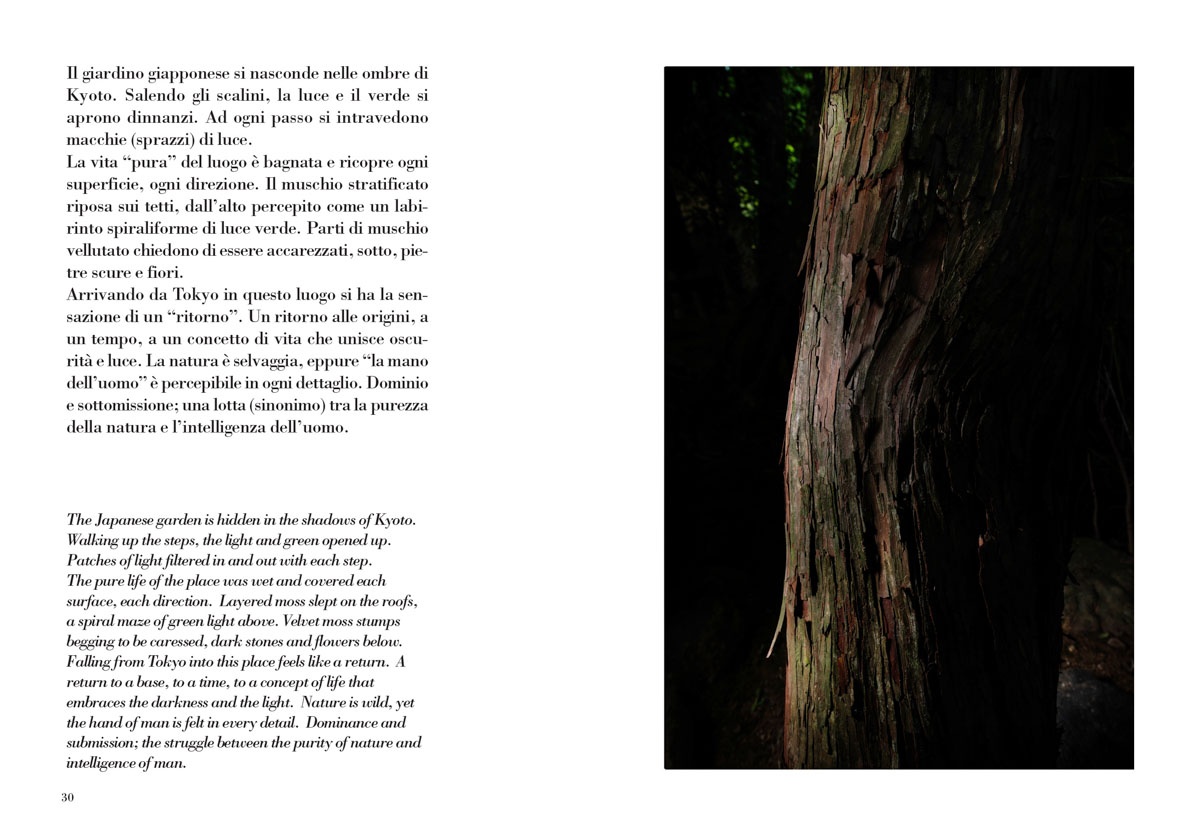

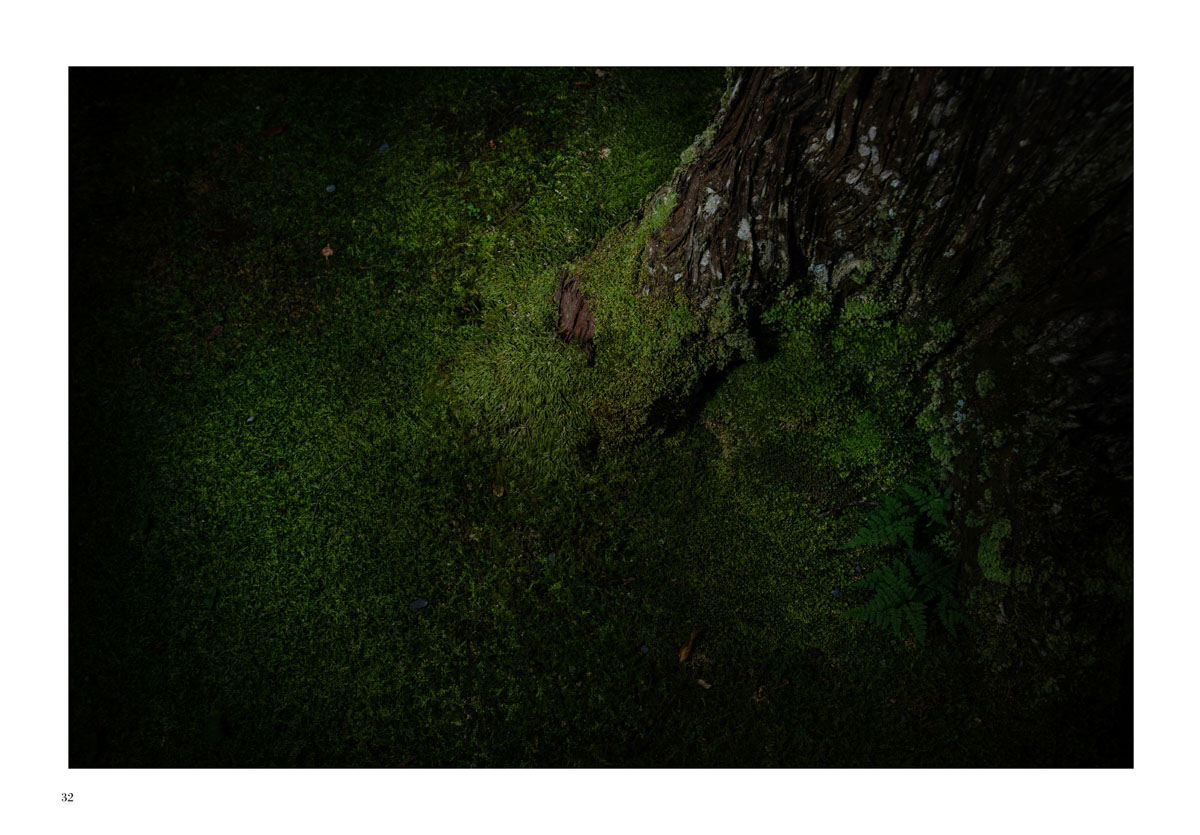

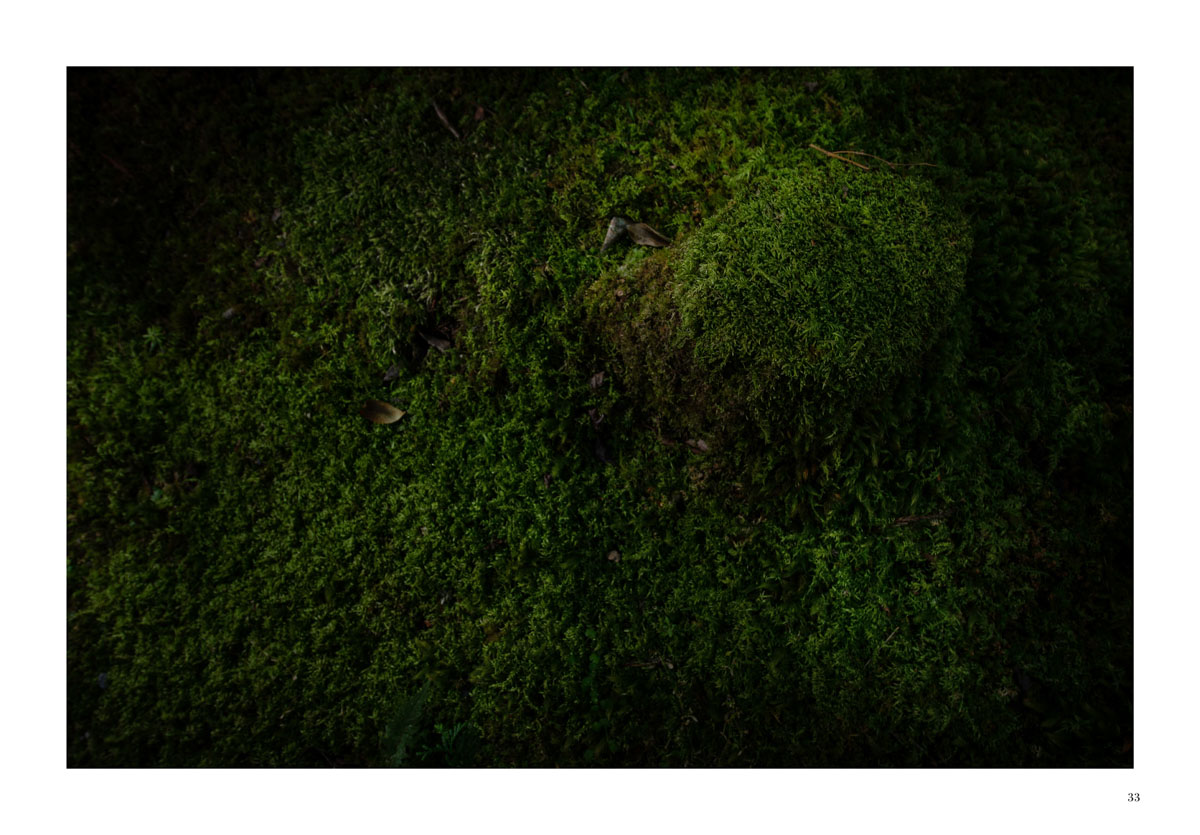

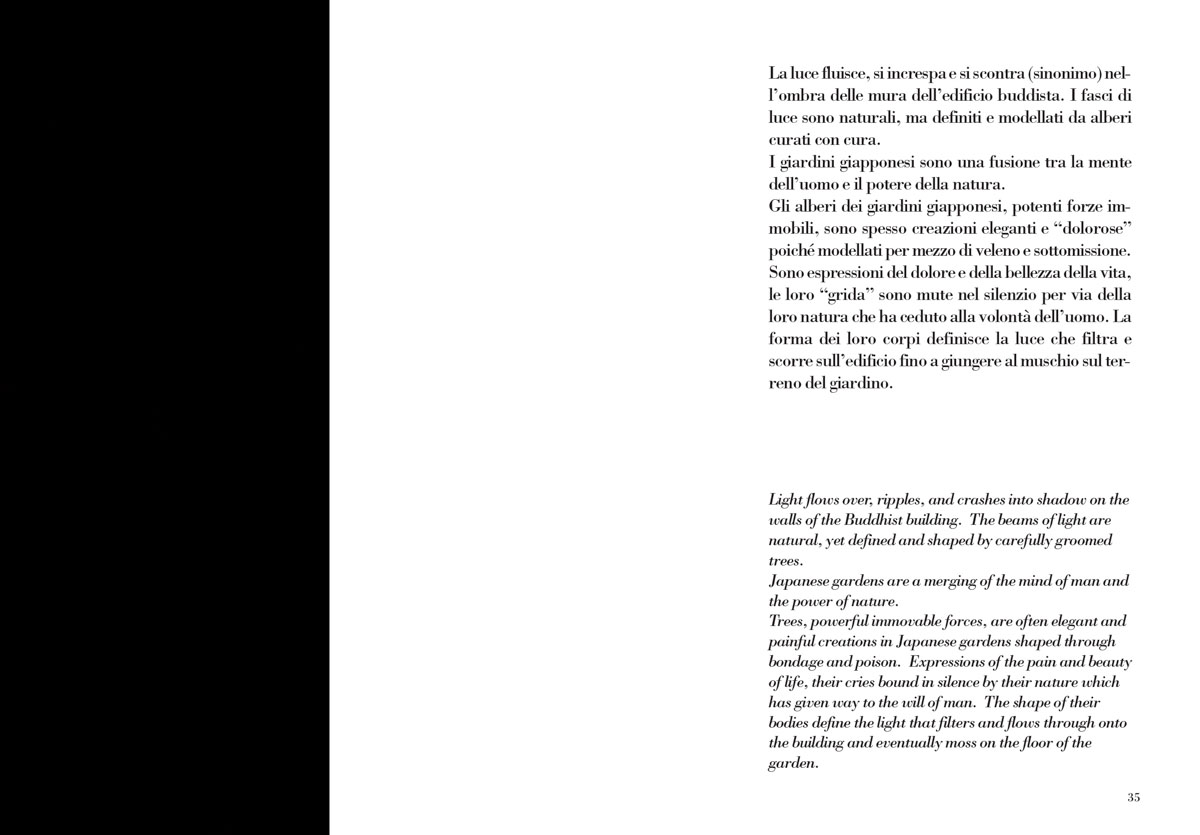

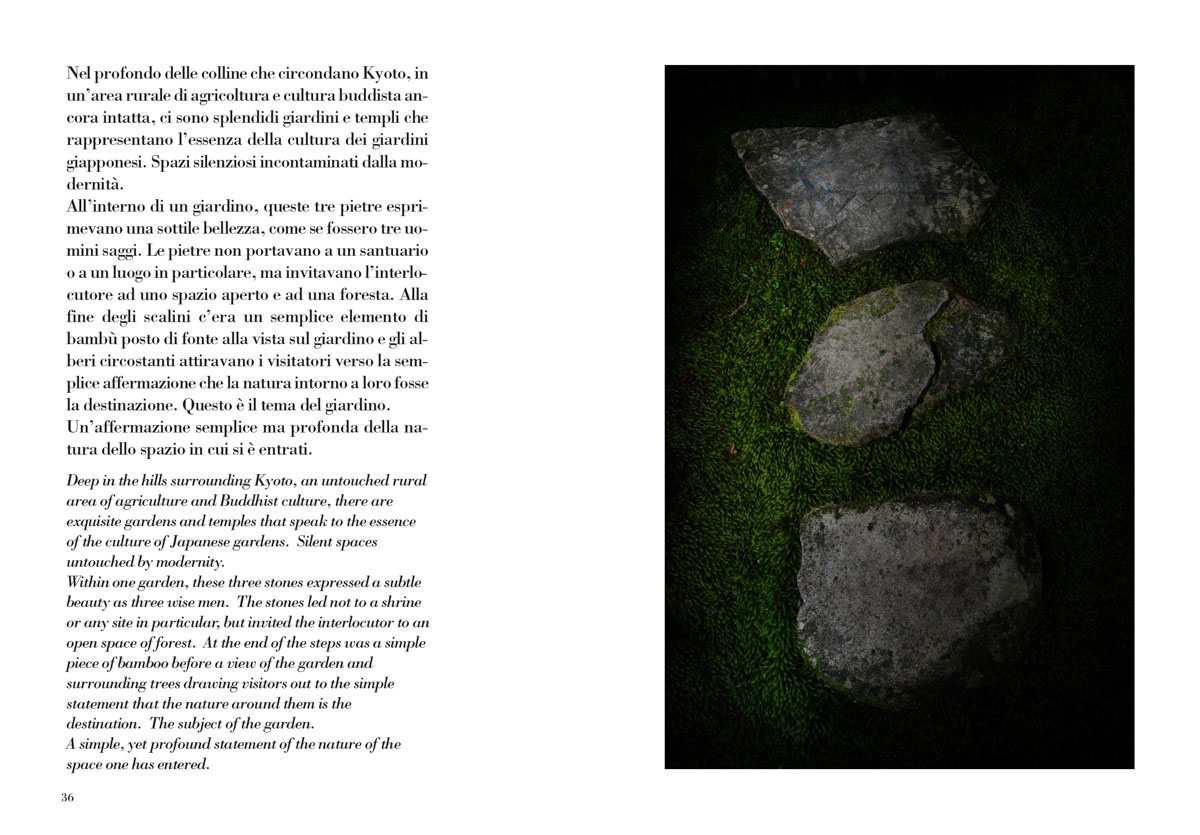

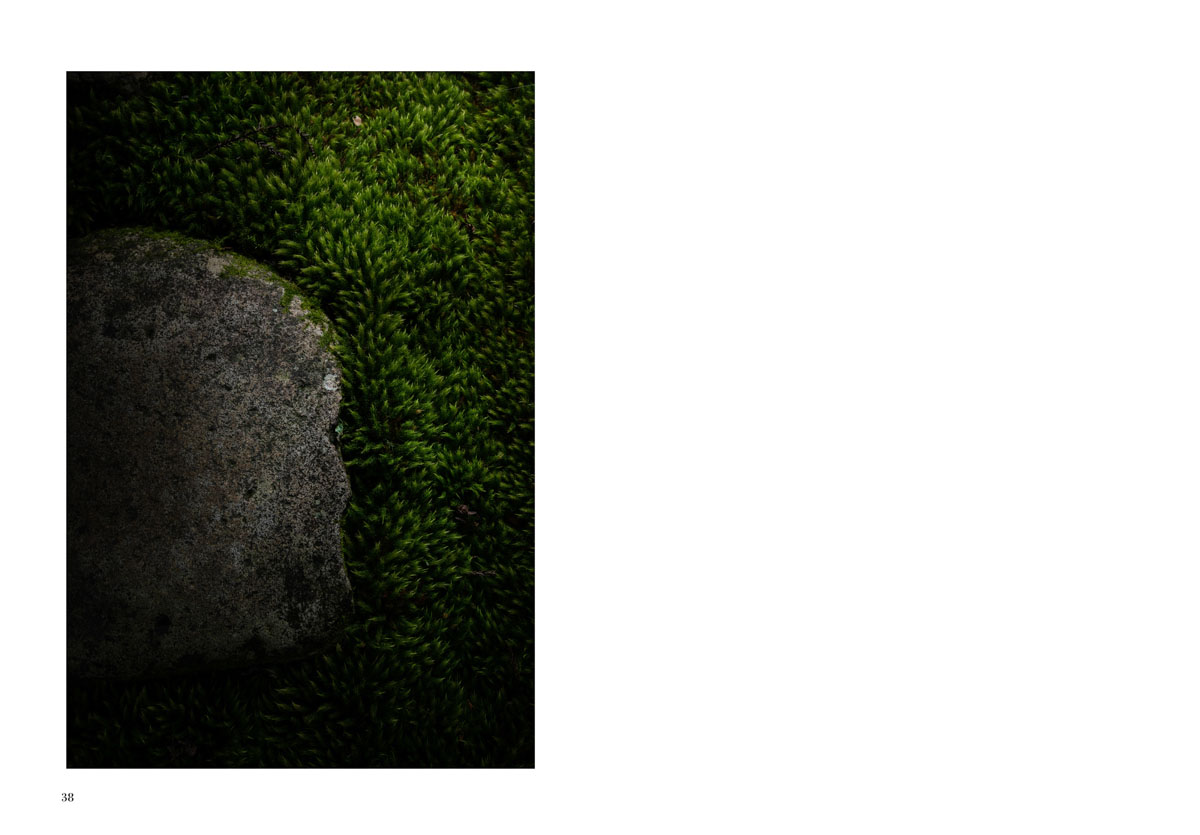

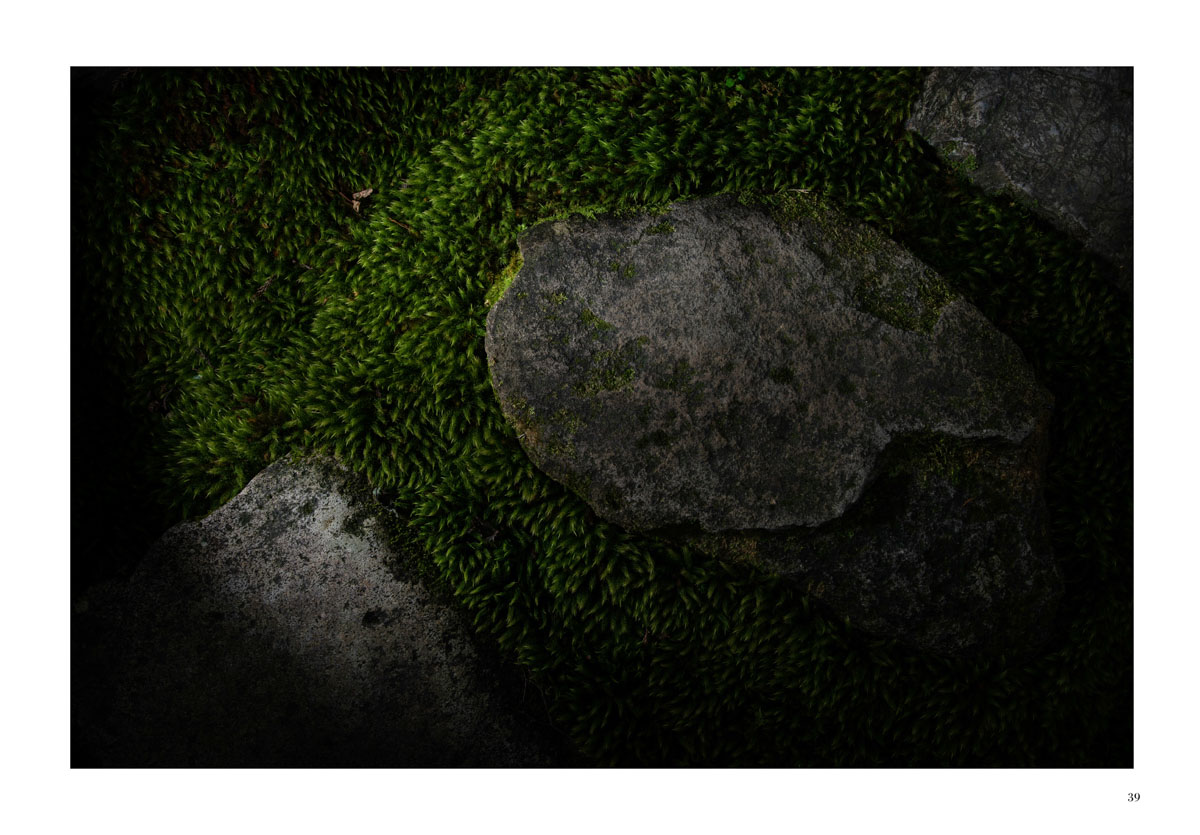

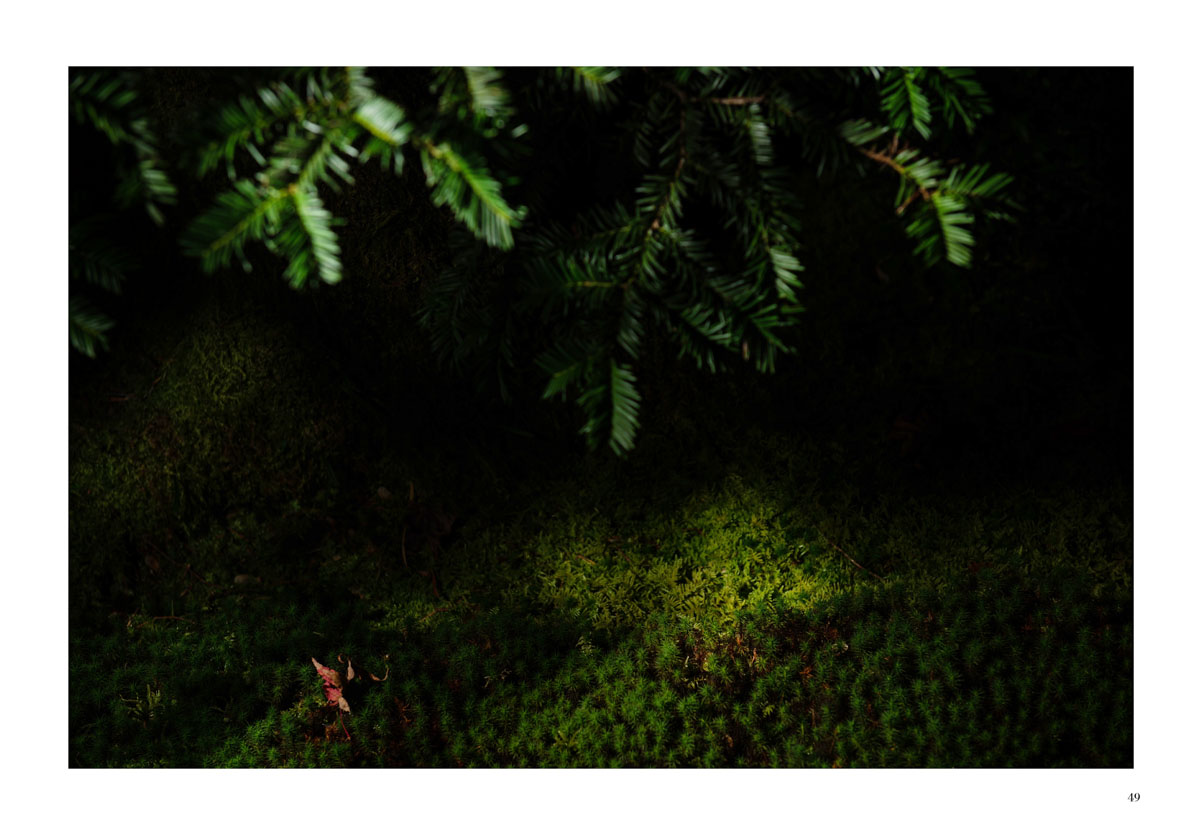

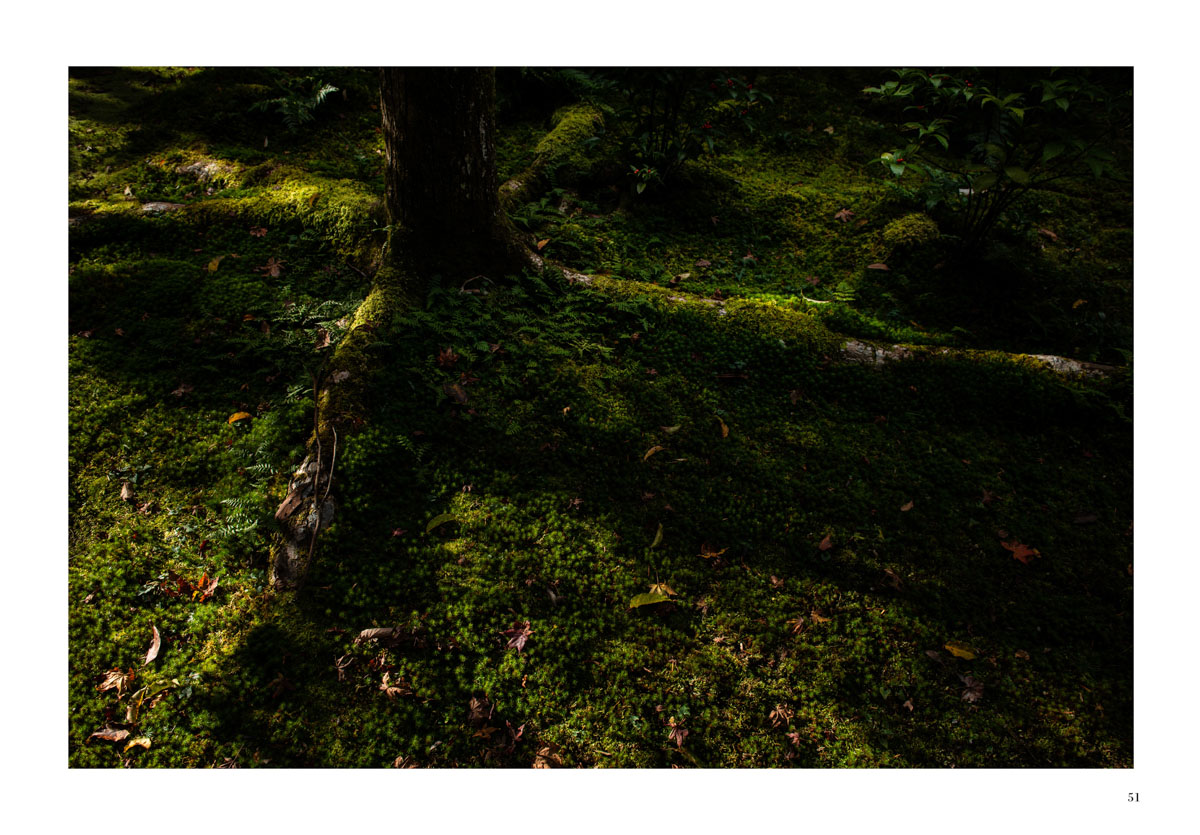

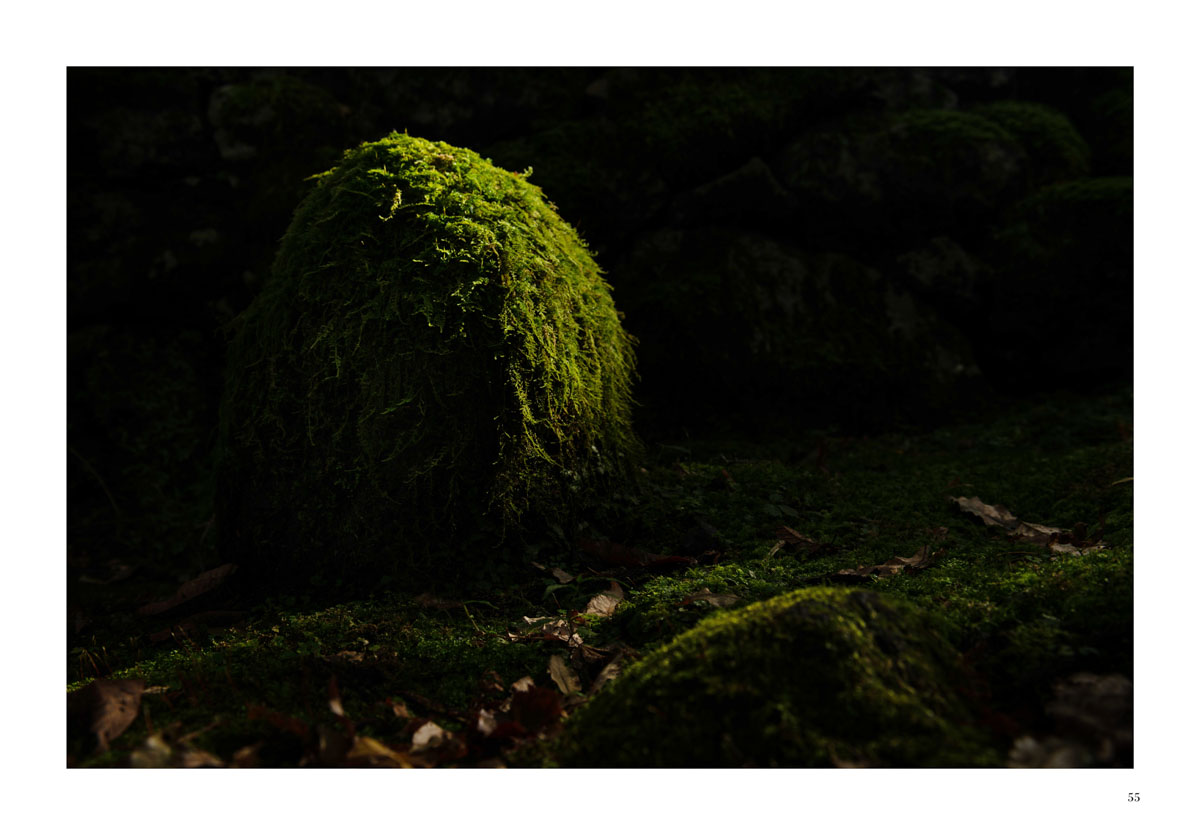

Upon entering, you are surrounded not by freedom as in a western garden created with the cultural concept of I, but a deep intimate psychological space that defines precisely where you are, where you are to go, and how you are to observe. There are no views, no vistas to distract. Instead ones perspective is forced down and in. This is one aspect highlighted in this photographic series, the perspective is primarily towards the ground, deep in details of the stones and moss. These stones are placed so that each step is defined, your conscious and unconscious unified with those who have walked here before you. The moss and nature in general is meticulously groomed and defined. Deep and green, the moss is delicate, moist, and only to be obverved, not stepped on. It is meticulously groomed by the gardeners of this space to fill the inner garden with an intimate silence. A silence to be experienced as part of a psychological uchi, aligned with all those who have also been here within the confines of the garden in accordance with the will of the designer and keepers of the garden.

This silence and depth is felt in the lighting of the photographs which are wrapped in shadow. Light is let in but carefully and intentionally as the gardener who intentionally grooms the moss. The light and shadows play on the idea of that which is revealed and hidden, that which is inside and out. This darkness, these shadows, are an important element of the photography series and a common theme in Japanese homes which are closely connected with the concept of uchi. In Praise of Shadows by Tanizaki, explains that the true beauty of Japanese lacquerware is revealed in the shadows and dim-light of the traditional Japanese house. “Darkness is an indispensable element of the beauty” says Tanizaki.[5] The concept of uchi and darkness are deeply connected, at the physical level, but also conceptually. An uchi space, whether one is refering to a home or garden or the self or social group, is dark and private.

A culture which defines the self as autonomous, as free, and individual would never create a garden such as this which distinctly defines the self through silence, intimacy, and constraints, and darkness. While a Western garden is easily viewable and open to interaction, a Japanese garden hides, and reveals through a play of light, shadows, and winding paths that never openly speak of its nature but play with the concept of self and secrets. The photographs in the accompanying exhibition “Shadows of Japanese Moss Gardens: Uchi- Soto” focus on this aspect of Japanese gardens, showing these gardens as a social-psychological space based on the Japanese cultural logic of the self, uchi. Here the Western concept of I is absent, devoured by the silence and shadows of the moss and unmoving stones that allow only one path, leading to an experience of the self as defined by this definitive Japanese dichotomy of uchi/soto.

[1] Benveniste, Emile. Problems in general linguistics. (Gables, Fla.: University of Miami Press, 1971), p.227.

[2] Bachnik, Jane and Quinn, Charles. Situated Meaning: Inside and Outside in Japanese Self, Society, and Language. (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 75.

[3] Bachnik, p.75.

[4] Benveniste, p.226.

[5] Tanizaki, Junichiro. In Praise of Shadows. (London: Vintage Press, 2001), p.23